To Wrap is to Love

Veronica Yang

See it On Campus: Level 2

Visitor Info

A series of paintings, sculptures, prints, and installations that embody the cultural heritage and women’s history of the Korean diaspora.

Migration has been a defining aspect of my life since childhood and throughout my four years at Emily Carr University of Art + Design, I was given the time to delve into the depths of personal and collective histories. Through my artistic endeavours, I’ve been dissecting and processing these narratives, unveiling layers of meaning through the deconstruction of motifs and symbols.

Trigger warning: mentions of sexual assault, death, and trauma.

Through my creative process of crafting, painting, sewing, and printing, I found a profound connection to my ancestral heritage as a Korean immigrant. Living and studying on unceded land has prompted introspection into my role as the daughter of a first-generation immigrant parent. With this as the first research question, I began to unravel family narratives and excavate the shared history of the Korean diaspora.

My Research Topic:

dissecting personal and collective trauma

Women’s history & women’s work

Korean diaspora studies

Girlhood & womanhood

Colonialism, trauma & intergenerational trauma

“Comfort women”

Symbols, symbolism, and motifs

Normalcy

The ability to engage in artistic expression and delve into my ancestral history is a privilege I do not want to take for granted. Reflecting on my family lineage just three generations back reveals traces of trauma stemming from colonialism, warfare, violence, and poverty. Yet, this narrative is not exclusive to my own but resonates across the broader spectrum of the Korean diaspora and beyond.

The fusion of quilting, painting, and color-driven storytelling resonates deeply within me. From childhood, I was drawn to tactile creation and the art of narrative construction. Learning to sew from my mother at age eight, initiated a language of expression that felt inherently natural. Paints, colour, and fabric seamlessly intertwine as an extension of my being, a second nature through which I articulate the essence of my girlhood and womanhood. Through visual storytelling, I aim to honour the tradition of women’s labour, artistry and technique passed down through generations. Furthermore, my exploration is centred on the concept of repetition, patterns, and the creation of a visual language that emanates from the individual which echoes to the collective consciousness.

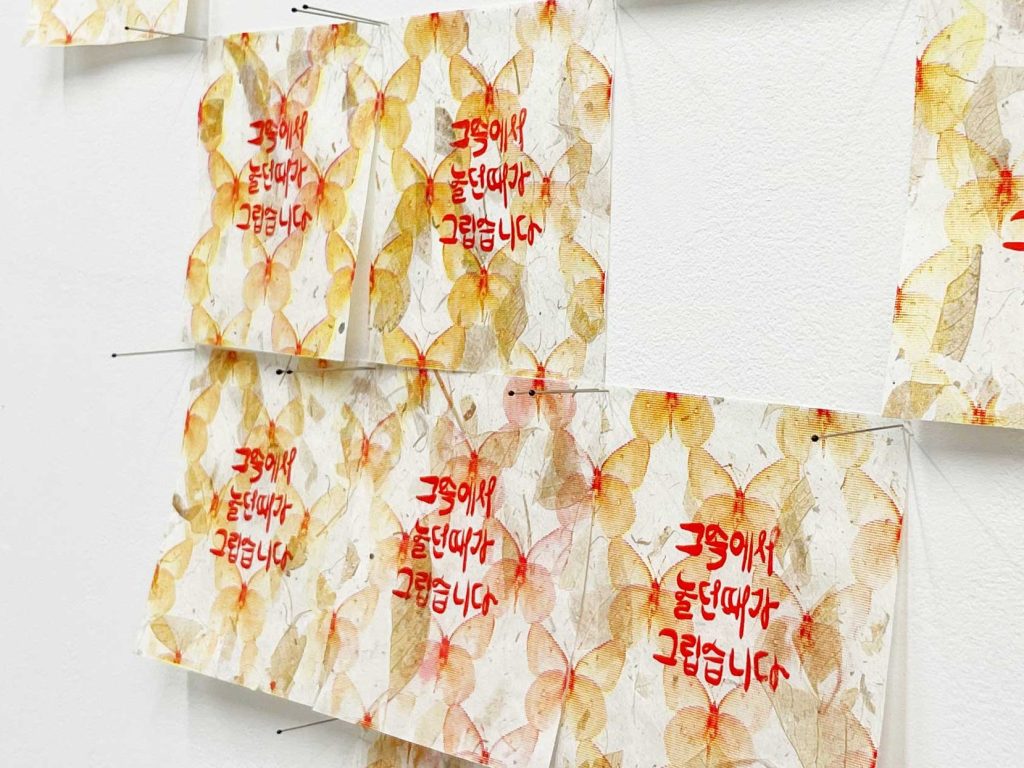

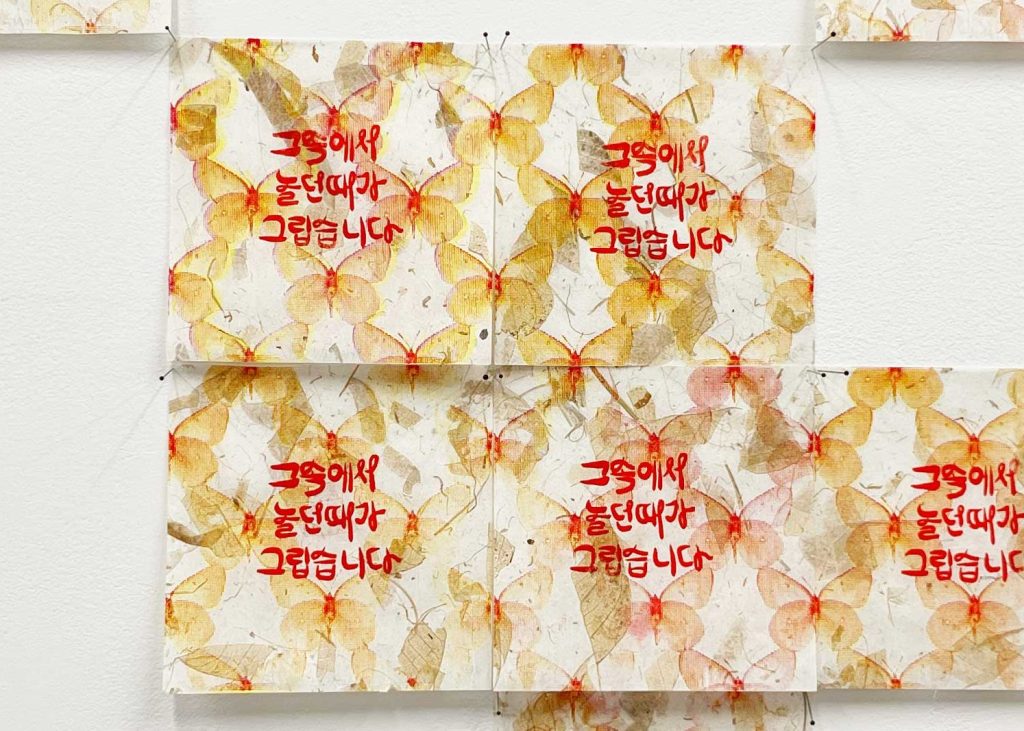

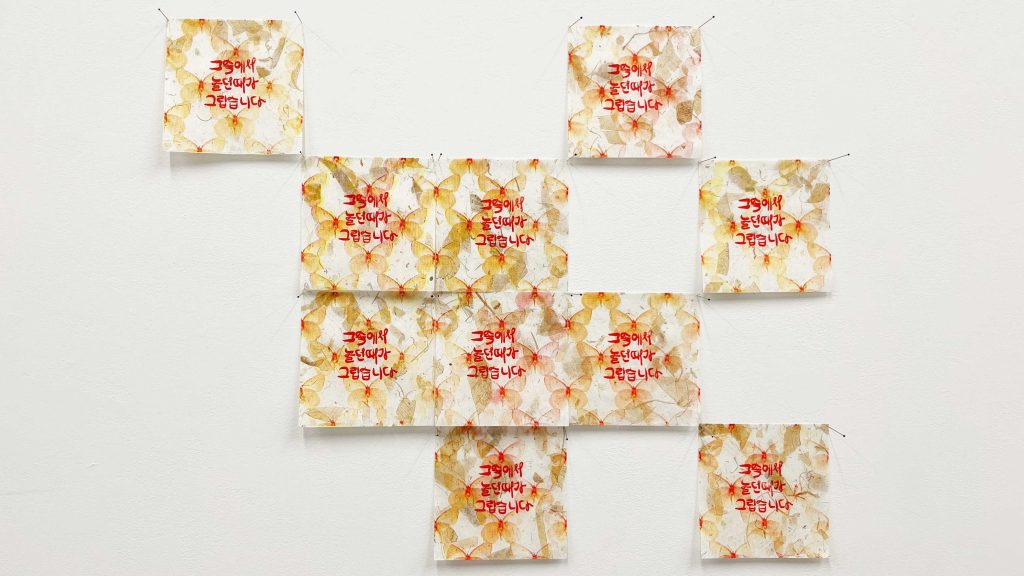

Butterflies & Comfort Women

Butterflies are often a symbol of freedom and love. However, traditionally, the depiction of two butterflies together often symbolized marital harmony, representing both male and female counterparts. This motif adorned various household items including folding screens, furniture, ceramics, wedding attire, and ceremonial robes. Additionally, as butterflies emerge during springtime, they carry connotations of wish fulfillment and the arrival of spring. Moreover, yellow butterflies are often used as a symbol of rebirth for “comfort women”.

With my subject matter so closely related to women’s work and womanhood. I couldn’t ignore the history and tragedy of “comfort women”. More than 200,000 Korean girls were forced into sexual slavery under the Japanese army and lived in “comfort stations” all across Asia. Approximately 10% percent of the women survived and returned to South Korea only to live as social outcasts. Korean women were not the only victims of this tragic event, young girls and women from the Philippines, Taiwan, China, Burma, Netherlands, Malaysia and Indonesia were also victims of this traumatic history.

This made me research deeper into the specific history of comfort women, the victims, and their testimonies. In 2023 the last victim passed away in Taiwan and the voices of 200,000 girls remain as ghosts. These victims, usually from low-income backgrounds, existed marginalized within society. Many remained unmarried, estranged from their families, and chose to carry their burdens in silence.

Moreover, the elder generation who grew up in a war-torn Korea never learned how to read until after the peace treaty. Amongst the illiterate elderlies, a significant portion were women. Only to later learn to read, write, and articulate their experiences through written language.

Gravity and Freedom

Numerous migrants depart from their native lands in pursuit of a more promising existence for themselves and their loved ones. Having myself resided in thirteen different cities and towns across three countries, I have observed that the transient lifestyle embodies a perpetual readiness to depart while being simultaneously prepared for settlement.

The bottari, as portrayed in Rest and A Spring Day, shows an elementary instrument wherein the fabric is utilized to encase possessions. Traditionally, a woman would balance a bottari on her head—a practice emblematic of many cultures.

Delving into the intricacies of migration and mobility, this concept challenges itself through the symbolism of stones with lightness against heaviness. Illustrating how migration and movement may be perceived as both burdensome necessities but also an avenue toward settlement and belonging. The act of carefully bundling one’s belongings into a single wrap and travelling across terrains signifies a process close to quilting—metaphorically stitching together disparate elements into a cohesive whole.

Ultimately, weight and weightlessness explores the duality of heaviness and lightness, both in physical and metaphorical dimensions. Through this juxtaposition, the artworks delve into the complexities of existence and identity, navigating the burdens we carry and the moments of liberation from their weight. Through various mediums and forms, the collection invites viewers to contemplate the contrast between gravity and freedom, inviting introspection into the forces that tether us to the land and those that allow us to transcend its bounds.

My motivation for delving into this historical root comes from a desire to illuminate the forgotten narratives of women’s history in the Korean diaspora. Yet, as both an artist and a woman, I was challenged of honouring these women authentically within the broader context of the Korean diaspora.

In my exploration of archival images, from pre and post-colonial Korea (around 1900s to 1960’s), I’ve discerned a predominant pattern: the majority, if not all, of these visual records, are captured through the lens of foreign observers—individuals with a distinctively Western gaze. This realization emphasizes the complexities inherent in the representation of my culture and its history, mediated by the gaze of curious, blue-eyed visitors.

Guided by these reflections, I used ambiguity, silhouettes, interlaying of images, and vibrant colour contrasts to weave a narrative that embodies a generation of lost voices and untold stories.

It is a narrative embodying the journey of a young girl, a woman, a daughter, and a mother.

Drawing from numerous testimonies and interviews of “comfort women” victims, a common longing emerges from the ladies. A yearning for normalcy—a desire for companionship, parenthood, grandchildren, and familial bonds. Above all, it’s a yearning to reclaim a sense of home within their bodies and minds. Through the empty silhouettes and blurry figures, we can only imagine what life could have been like before.

Furthermore, storytelling is an integral element in my work. It is through the preservation of narratives and lived experiences that remembrance endures. Trauma, history, and oppression intertwine, forming a cohesive narrative like interlocking puzzle pieces, one story cannot be told without the other.

Though it may sound idealistic, I earnestly hope that in another life, these women find solace in a life untouched by the pain they endured in this one. Unfortunately in this life, we are only left to remember their stories and carry their stories for a greater goal of reconciliation and peace. Without the continuity of the passing down of stories, what truly remains of remembrance?

The text “그속에서 놀던 때가 그립습니다” translates to “I miss the times when I played in there.”

Installation Photos

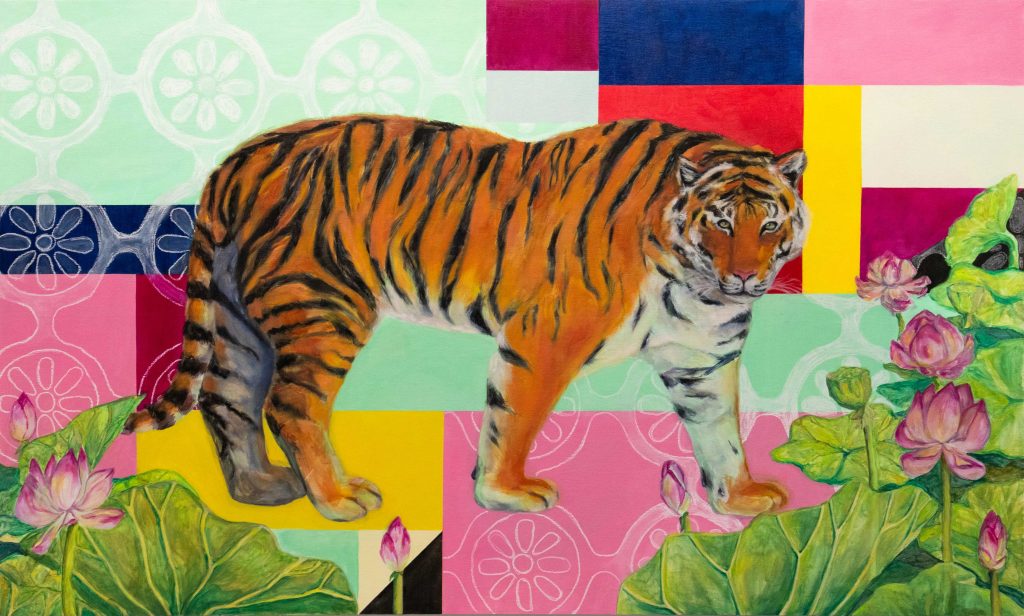

More on symbols and symbolism

Symbols and symbolism are prevalent across diverse cultures, yet in my research of archival imagery, I’ve observed the gradual disappearance of many symbols and motifs from contemporary discourse. This raises questions about the criteria distinguishing the contemporary from the historical or traditional. I’ve delved into the dichotomy inherent in the visual language of symbols within Korean tradition.

Symbols and motifs permeate various aspects of life, from attire to furnishings and even architecture. Korean traditional arts and culture boast an array of embellishments and decorative designs imbued with contextual significance. Through my investigations, I’ve unearthed patterns that unveil layers of meaning. Many of these symbols and motifs once adorned domestic articles, serving as omens of prosperity, fertility, and well-being. For instance, items intended for female use often bore symbols indicative of a blissful marriage, abundant offspring, and robust health for childbearing. However, in today’s societal landscape, notions of childbirth and marriage have evolved significantly, altering the potency of these symbols. They no longer carry the same influence as they did when employed as protective talismans. Through the recreation or reinterpretation of these symbols, I aim to ignite a revitalized visual language that resonates with the same power and resilience in the contemporary context.

To all grandmothers, mothers, and daughters who were left forgotten.

Past works

Follow me on Instagram and feel free to contact me if you have any questions!

@veronicaartss